Understanding Quality of Life in High Digital Device Users Who Are Treated With Systane Hydration PF

Abstract

Purpose

To understand the impact of Systane Hydration PF on dryness symptoms and quality of life in digital device users and to determine if participants prefer either the unit-dose or multi-dose dispensing system of Systane Hydration PF.

Materials and Methods

This 2-week, three visit study recruited regular digital device users. Participants were required to score ≤80 on the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) Quality of Life (QoL) Work domain and between 13 and 32 on the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire. Participants were randomized to either Systane Hydration PF unit-dose or multi-dose for 1 week and switched to the alternative dosing system for the second week. Participations were evaluated by completing the full IDEEL-QoL module and OSDI questionnaire at each visit. Likert surveys were completed to probe dispensing system preferences.

Results

Thirty participants with a mean ± SD age of 28.6 ± 12.0 years (70% female) were recruited. Participants had significant improvements in all three IDEEL-QoL domains as well as in OSDI scores (all p < 0.0001). Participants had similar preferences for the two dispensing systems, though they were more likely to indicate that they thought that the multi-dose bottle was more environmentally friendly than the unit-dose vials.

Conclusion

Digital device users with dry eye symptoms had meaningful improvements in eye comfort and quality of life scores after being treated with Systane Hydration PF for 2 weeks. Participants did not have a clear dispensing system preference suggesting that the best dispensing system may depend on the patient.

Introduction

While high-powered computers and digital devices have greatly improved many aspects of modern life, such as improved social connections, providing lifesaving assistance, and making our transactions more efficient,1 the pervasive use of digital devices has caused some patients to develop a condition known as Digital Eye Strain (DES), which is also known as computer vision syndrome (CVS). DES is a condition where patients experience eye symptoms, which can be subcategorized as vision-related, oculomotor-related, ocular surface-related, environmentally related, or device-related.2 Seguí et al have specifically determined through an extensive literature search that CVS/DES symptoms include burning, foreign body sensation, tearing, excessive blinking, eye redness, eye pain, heavy eyelids, dryness, blurred vision, double vision, poor near focusing, photophobia, glare and halos, worsening vision, and headache.3

Extensive digital device use is no longer an employment-specific challenge, because digital devices are now common and socially expected during many home and leisure activities.4 Digital device use can produce a myriad of symptoms,2,4–6 with many of these symptoms also being indicative of dry eye disease (DED). Thus, it is not surprising that there is an established relationship between DED and DES.2,4–7 DES symptoms have been reported to be as high as 93% in digital device users depending upon how DES is defined.2,4 While the etiology of dryness symptoms in DES are probably multifactorial and likely include contact lens wear, incomplete blinks, tear film instability, and increased friction, much of the dryness symptoms in DES are likely due to tear film evaporation secondary to having a reduced number of blinks per minute while using digital devices.2,7 Since much of the ocular symptoms associated with DES likely stem from excessive tear evaporation, artificial tears have become an accepted treatment for dryness symptoms in DES patients.2,4

Systane Hydration PF (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA) is a preservative-free, artificial tear that contains water-loving sodium hyaluronate and the viscosity enhancing agent hydroxypropyl guar. While Systane Hydration PF should in theory improve the dryness symptoms and subsequently the quality of life of patients who have DES, this clinical application has yet to be tested. This preservative-free drop furthermore is available in both unit-dose and multi-dose drop system options, but it is unclear if patients perceive a difference between these two dispensing systems. Thus, the purpose of this study was to recruit participants who have DES who also have mild-to-moderate dry eye symptoms and to treat them with Systane Hydration PF to determine how regular use of Systane Hydration PF over 2 weeks impacts a patient’s ocular symptoms and overall quality of life. This study secondarily compared the participant’s experience with the two Systane Hydration PF dispensing systems because this information could improve compliance and subsequently treatment effectiveness.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This 2-week, three-visit study was conducted at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL, USA). A total of 30 participants were recruited. Thirty participants were deemed appropriate since 29 participants yielded sufficient data to understand patient reported outcomes in a recent study completed by the lead investigator.8,9 Adult (>18 years) participants who answered yes to the following two questions and used digital devices (eg, computers, tablets, or smartphones) ≥8 hours per day were recruited:

Are your eyes dry, irritated, or itchy or do they burn while using a digital screen, like a computer or smartphone? Yes or No

Eye fatigue is the physical discomfort of your eyes after spending periods of time throughout the day in front of a digital screen, like a computer or smartphone.10 Do you have eye fatigue based upon this definition? Yes or No

Participants were also required to score ≤80 on the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) Quality of Life (QoL) Work domain to ensure that they had clinically meaningful symptoms,11 and they were required to have an Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score between 13 and 32 (inclusive) to ensure that they had mild-to-moderate dry eye symptoms, which is the typical indication for artificial tear monotherapy.12,13 Each subset of the IDEEL-QoL questionnaire has a 0 to 100 range with higher scores being better. The OSDI questionnaire likewise has a 0 to 100 range; however, lower scores are better. Participants were excluded if they had worn contact lenses in the past week, had a known systemic health conditions that is thought to alter tear film physiology, had a history of ocular surgery within the past 12 months, had a history of ocular trauma, active ocular infection or inflammation, were currently using isotretinoin-derivatives or ocular medications, were currently using a dry eye treatment other than artificial tears, were currently using more than 4 drops of artificial tears per day in each eye, or if they were pregnant or breastfeeding.14 If a participant was using artificial tears or rewetting drops, they were required to refrain from using them for at least 24 hours before their baseline visit, and they were only allowed to use Systane Hydration PF during the course of the study. No contact lenses wear was allowed during the study.

Surveys and Clinical Tests

This study was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04837807). It was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Institutional Review Board (IRB-300007063), and it followed the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants were asked to bring their spectacles to the study visit and to adhere to the contact lens exclusion factors described above. The first visit commenced with reviewing the IRB approved screening form to ensure that they still qualified for the study. The OSDI questionnaire was completed, and it was confirmed that they had a score between 13 and 32 (inclusive). The participants then completed the IDEEL-QoL Work questionnaire, and it was confirmed that they had a score ≤80. Non-eligible participants were dismissed. Participants who meet all study criteria were enrolled following informed consent.

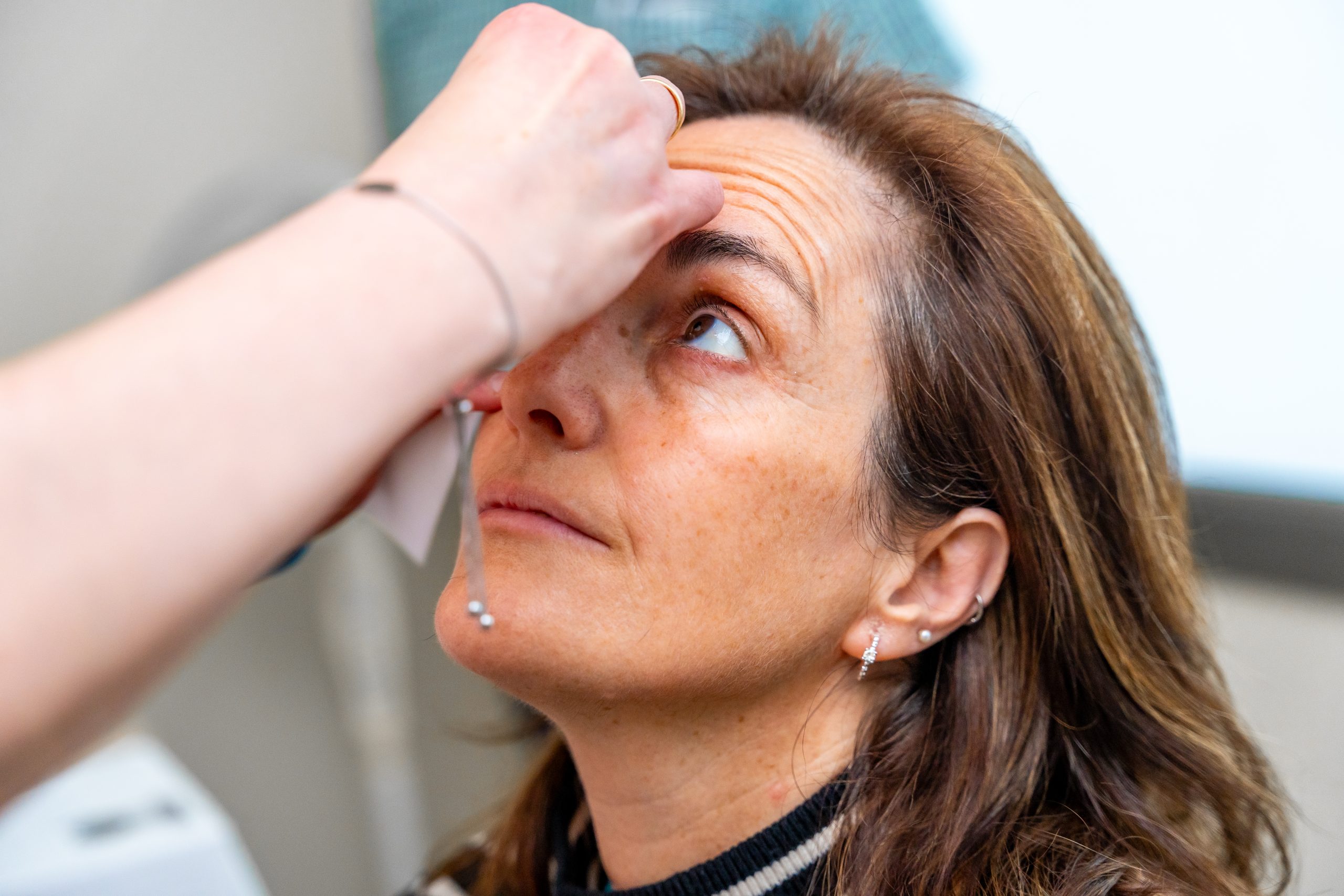

Participant demographics were collected (age, sex, race, ethnicity). The remaining two subsections of the IDEEL-QoL questionnaire were then completed (Daily Activities and Feelings).15 Visual acuity was measured with a Bailey-Lovie high-contrast Logarithm of the Minimum Angle of Resolution (logMAR) chart with their presenting correction if applicable. A slit-lamp biomicroscope was used to monitor ocular safety. After completing entrance testing, participants were randomized with Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) to determine if they would start with Systane Hydration PF multi-dose or Systane Hydration PF unit-dose.16,17 Participants were educated that they should use Systane Hydration PF at least four times per day in each eye. During this education session, the participants were also given a daily log to record the number of drops used each day, their eye comfort throughout the day, and the duration digital device use by type across the study. When comfort was being evaluated, it was done so with a 0 to 100 visual analog scale (VAS). Higher scores were more comfortable.

When participants returned for their one-week visit, they repeated the OSDI questionnaire, all three subsets of the IDEEL-QoL questionnaire, visual acuity, and an evaluation with the slit-lamp biomicroscope as described above. The participants then completed an investigator-designed Likert questionnaire based upon the work of Denis et al that probed their experience with the drops.18 This questionnaire also queried if participants had any mobility issues since the Likert questionnaire was aimed at understanding how the participants perceived applying the drops. The compliance log was collected at this visit, and they were given a new compliance log to be completed over the following week. Participants were then given the alternative drop delivery system, and they were released until their follow-up visit. No washout period was deemed necessary since participants were using the same drops.

When participants returned for their two-week visit, the same testing was completed as at the one-week visit; however, the investigator designed questionnaire included a question that specifically asked the participants to select which dispensing method they preferred. After the completion of this testing, participants were released from the study.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with SAS Version 9.4 (SAS; Cary, NC, USA) or Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Means and standard deviations (SD) were presented to understand data trends. ANOVA and chi-square tests were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The patient reported outcomes questionnaire data were analyzed to determine the frequency of each response, and these data are presented as percentages. When analyzing the treatment effect of Systane Hydration, the data were analyzed chronologically, but when dispensing methods were being analyzed, data were sorted by dispensing method.

References

news via inbox

Subscribe here to get latest updates !